For Starters

Full of beginnings without ends. . . .

—Ursula K. Le Guin

The first work of Ralph Lemon’s I saw was How Can You Stay In The House All Day And Not Go Anywhere? in 2010. Moving between the death of a lover and the dis-appearing rituals of a Southern community formed in the aftermath of slavery, the work was at once personal and epic, idiosyncratic and laden with historical gestures. In it I found something I had been longing after: brutal, grief-stricken, How Can You Stay’s emotions came before the explanations for them. When I first met Ralph, two years later, I asked him, “What does it mean to you now?” He answered with silence.

For Ralph, evasion and erasure are counterintuitive; they mark history’s traces and court the past’s return. History—with its discrete epochs, nameable masses, and willful actors—is neither salve nor refuge for those who lie beyond its rules. But by holding onto and abstracting the objects, gestures, and words of those around him—anonymous and known—Ralph extends the timbre of a voice or the chill of an emotion for us to touch. Individual voices bleed into one another as Ralph steals words first uttered offstage and then asks someone else to speak them again. Yet, despite their suspended reference, the words always retain their specificity. The tracks he leaves for us are his Easter eggs; perhaps these truths are already being mythologized in this book’s origin story.

Attics’ Voices

Certain scenes, gestures, and figures recur across Ralph’s forty years of dancing, writing, and making art.

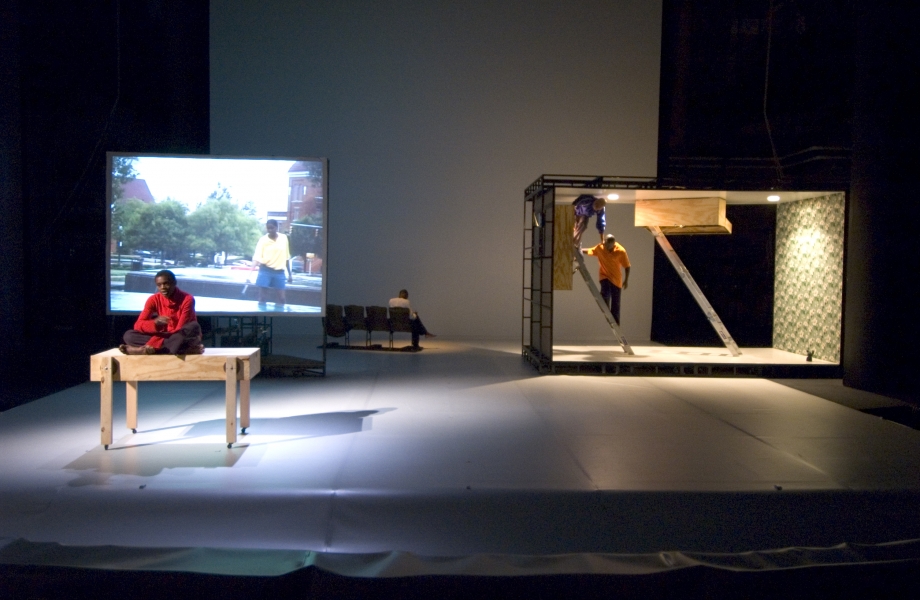

Consider in Ralph’s work since the early 2000s the role of attics, secret spaces where histories are often packed away. The 2004 performance Come home Charley Patton (fig. 2) features dancers Djédjé Djédjé Gervais and Darrell Jones interacting in what Ralph calls the “Attic Space,” an open-frame box on wheels, to which the sculptor Nari Ward added retractable trip ladders that the performers climb up and fall down.

The attic, videotaped and then looped back to the audience on a large flatscreen monitor, is a stage within a stage. In front of the monitor, Okwui Okpokwasili, Ralph’s self-appointed avatar, describes her first sexual encounter, which also occurred in an attic, it too accessible only by ladder.

In 2006, Ralph reconstructed the “Attic Space” as a cinema at the center of his gallery installation (the efflorescence of) Walter. This steel-and-plywood “Attic Space”—adorned with wallpaper and white plastic chairs—housed a video fea-turing Ralph giving off-screen prompts to Walter Carter, a former sharecropper turned gardener. Carter was first introduced to Ralph in 2002 as the oldest living resident of Yazoo City, Mississippi, and, for the next eight years, acted as another one of the choreographer’s muse-doppelgängers.

The metal trusses and sprung floor of the “Attic Space” resemble the struc-ture in yet a third work, the 2014 Scaffold Room (fig. 3), which Ralph called a “lecture-musical” among his collaborators. A stage on wheels, this attic, equipped with everything from a collapsible video screen to a bed, accommodates the work’s two performers, Okpokwasili and April Matthis, as well as video record-ings of Carter’s wife Edna, as they conjure a range of black female archetypes across the color line and gender matrix, from Moms Mabley to Amy Winehouse, from Kathy Acker to Samuel R. Delany. The structure, with its RV–like auton-omy and mobility, demands different supports depending on where it’s placed.

Where do Ralph and his things belong? Migrating from proscenium stage to gallery floor to a kind of proscenium in itself, his garret has gone by different names: sculpture, set, installation, stage, and, once more, sculpture. At times the attic’s context has emphasized its relationship to narrative and certain forms of dance theater; at oth-ers, its frame has allied it more closely with what Frank Stella described as “What you see is what you see”—an aesthetic of truth in materials associated with Minimalist sculpture. Rather than setting these strategies in opposition, Ralph conjoins them, sourcing, for example, the attic’s set furniture and wallpaper from a secondhand store, while using foam to make pallets that resemble the finish of cut wood In this way, the attic confuses clear-cut distinctions between truth and artifice, original and repro-duction, naturalism and expressionism—binaries that have historically separated time periods and art-making disciplines (so-called postmodern dance theater in the United States in the 1960s and what transpired after, for example), as well as forms of cultural posterity (the modern art museum’s collection that acquires and recontextualizes objects according to hierarchies of taste and value, versus the archive, which fore-grounds the organization of materials according to their original sequence). Rather than prioritize one over the other, Ralph situates his work in both and neither of the categories he invokes. Equipoise, after all, is what keeps us from falling down.

Importantly, Ralph’s building materials and adornments conjure the idea of a home even as the juxtapositions he creates trouble the notion. The home, a longtime touchstone for debates around black and feminist spaces alike, has been invoked as everything from refuge, site of bondage, place of work, repro-ductive sphere, and zone of exclusion. French philosopher Gaston Bachelard writes about the house as a body of images in which the attic is filled with memories of solitude and creativity: “We return to them in our night dreams. These retreats have the value of a shell. And when we reach the very end of the labyrinths of sleep. . .we may perhaps experience a type of repose that is pre-human; pre-human, in this case, approaching the immemorial.” At once melancholically absent and indelibly present, Bachelard’s attic is the house’s psyche—indifferent, animal-like.

Within the cultural history of the black Atlantic world, the attic has been a particularly fraught space, simultaneously a place of captivity and flight. Harriet A. Jacobs’s antebellum slave narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself (1861), narrates a condition of freedom as simultaneously won and lost during the seven years she hid in a small attic in Edenton, North Carolina. Jacobs’s attic is both an extension of the bondage of slavery and, as she referred to it in one of the novel’s chapter titles, the “loophole of retreat” from which she surveyed her master and watched over her children. Consider also Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre: An Autobiography (1847) and its fictional character, Bertha Antoinette Mason, the first wife of Eyre’s husband Edward Rochester and a Jamaican-born white woman. Taken to England, where she is locked in an attic Mason eventually commits suicide. In postcolonial writer Jean Rhys’s retelling of Mason’s story in Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), Rhys renames her protagonist by her birth name, Antoinette Cosway, and ends the story with Cosway narrating her own experience in the attic: “There is one window high up—you cannot see out of it.” While Rhys’s ending is no less tragic than Brontë’s, in narrating Mason’s story across two continents, in the first-person, and from the author’s twentieth-century position, she portrays Jamaica and England, the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, captivity and liberty, as intimates of one another.

Ralph’s crawl space, like Jacobs and Rhys’s before him, is a vexed site that he returns to and reinhabits, as if to enter into a historical scene made coeval with the present. With each iteration, the idea of an original attic diminishes and is replaced by his rewriting and its multiples. Across Ralph’s three works, the attic is a space both of intimacy and publicness, a protective yet transparent environment for the inquiring viewer who looks in from outside. It is also a space where its protagonists—Okpokwasili, Matthis, and Carter—can perform and indeed assemble a sense of self from the scripts they construct with Ralph. Their belonging—like the attic, located at the most remote part of a home—is contingent upon another person and lies at the limits of identification. Ralph traverses these edges as he moves between disciplinary homes—theater, gallery, publication—reshaping codes at each location, deferring his alignment with any one.

Down: A Short History

The origins of authorship are often discussed along nearly Biblical or Oedipal lines, as in fathers, or occasionally mothers, who beget offspring with fraught resemblances to the generation before them. Yet when artistic genealogies are described using lateral relations—as in brothers or sisters perhaps, or spores dis-persed by the wind—lines of influence that move in multiple directions replace notions of descent. Authorship, like kinship, involves assuming somebody else’s voice in order to have your own. It entails getting inside someone else, which is always physical, a temporary violation of another’s bodily integrity. But being inside someone else certainly does not make this person yours; in fact, it more likely means that you belong to him or her, if only for a passing moment. The genealogy of Ralph’s artistic practice is full of such lateral relations, many of them unclaimed or unexpected.

Bruce Nauman, curiously, is one. In 2003, while Ralph was working on Patton, he was invited to perform at the opening reception for the exhibition How Latitudes Become Forms: Art in a Global Age at the Walker Art Center. For the occasion, Ralph recreated Bruce Nauman’s 1968 Wall/Floor Positions (fig. 6). The idea had emerged from a Patton workshop in which Ralph had asked his collaborators to bring in cultural texts that don’t signify as black; together, Ralph proposed, they would “blackify” the selected works. Ralph brought in Nauman’s now germinal piece. The black-and-white video, which Nauman described as being “about dance problems,” features the artist, alone, dressed in a white T-shirt and black jeans. Enacting the work’s title, Nauman creates distinct poses between the wall and floor of his studio. Over time, as he moves his body, the wall and floor appear to switch positions so that the vertical plane looks to be horizontal, as if the video camera has turned ninety degrees; as if Nauman, even though he does noth-ing more than stand, bend over, and crouch, begins to hang, or fall, upside down. The wall and floor shift positions while the artist’s white, boyish, barely affected body remains constant, the meter for his evenly timed adjustments. It is no longer the floor that supports the wall but Nauman; his body becomes the ground, and the architecture emerges as figure. Context becomes theatrical content.

For the Walker performance, Ralph used a plywood structure made up of a simple wall and floor and, with Gervais, enacted his version of Nauman’s work. Each of their movements is distinct, Ralph’s more virtuosic than Nauman’s pedestrian motions, and Gervais’s rather faithful to the earlier artist’s, albeit through his own vernacular. In the video documentation, the text on Gervais’s T-shirt, handwritten in thin, black magic marker, is discernible: “Bruce Nauman is black.” Ralph’s observation is in part an art-historical argument about the space Nauman has created for himself to consider race both culturally and aesthetically. Throughout his body of work, Nauman refers to blackness as at once a color and a social fact, from his constant evocations of “black death” in his works on paper, neon sculptures, and mobiles, to his four Art Make-Up films, made between 1967 and 1968, in which he applies various pigments, including black, to cover his upper body and face.

But Ralph’s recreation of Nauman’s work is more than art-historical refer-ence. Pointedly, Ralph inverts the typical direction of racial appropriation and theft, claiming Nauman as an artistic brother across the color line. In restaging the work with a beginning and end (Nauman’s was played on a loop), a live audi-ence, and a duet with two black men, Ralph emphasizes the theatrical, social, and racial content already latent in the earlier artist’s work: Nauman’s falls, safely exe-cuted in his studio, echo the falls of African Americans from hosings, bombings, lynchings, and assassinations outside his studio walls. Ralph considers precisely that which was presumed outside the frame of the original performance, further expanding Nauman’s spatial shift to include the ground of racial protest underly-ing and produced by artistic freedom.

Steve Paxton is another point of contact between Ralph and an artistic predecessor, in particular his 1972 dance Magnesium. The work was performed by a group of men in a gymnasium at Oberlin College, the culmination of a three-week workshop, and the dance from which Paxton would later develop his concept and practice of contact improvisation. The falling, rolling, and colliding that characterize the majority of the dance—what Paxton called a “high-energy study”—temper as the work ends with five minutes of standing, or “small dances,” Paxton’s term for the choreography’s stillness.

Although the two scales of movement are visually distinct, both alert performer and viewer alike to the effect of gravity on the body. Indeed, for Paxton, an exploration of gravity animates the work: “I just wanted to be able to leave the planet and not worry about the reentry. In other words get up into the air in any crazy position and somehow have the skill to come back down without damage.” Preparation, bodily intelligence, and timing diffuse the risk in the act of falling by mediating the transfer of energy from the body’s vertical plane to the floor’s horizontality. Paxton’s attempt in Magnesium to shift from one plane to another informed his later development of “the sphere,” what he calls the space around the body from which one can peripherally gather information: “The sphere is an accumulated image gathered from several senses, vision being one. . .But skin is the best source for the image because it works in all directions at once.”

Although the connection between Lemon and Paxton’s Magnesium may not be immediately apparent, Paxton’s claim that, in making an image, touch might be more determinative than sight suggests the two artists have more in common than appearances let on. Ralph’s “Ecstasy” makes this case most clearly. Both Magnesium and “Ecstasy” share an interest in suspension—what Paxton calls “the passage from up to down” and Lemon describes as “falling, not up or down.” Might we deduce from this that they feel like one another? To be inside of either would be to experience spinning around a center, or swaying side to side, or having a body pressed close to your own, or risking physical harm. But we might also go further and argue that Magnesium and “Ecstasy” not only feel like each other; they also feel each other. Which is to say that Paxton and Lemon touch one another; that the aesthetic and social capacity of one dancer is expanded, extended, repeated, and refracted by the other.

What would eventually become Paxton’s contact improvisation, like what would eventually become Ralph’s no-dance, relied on memory, on what had happened before. (Paxton has cited several origins for Magnesium including studies in Akido, a previous idea for a solo, a former workshop with students, and a perfor-mance in New York.) The role of memory in contact improvisation is paradoxical: on the one hand, Paxton observes that “memory of past judgments tells me that pre-judging is not secure”; on the other, he recounts how he decided to learn falling skills, which have since become muscle memories, because he “figured [his] chances of survival were greater with these skills than without.” Too little mem-ory kills a work; too much memory makes it unnecessarily dangerous.

Memory is paradoxical for Ralph too. In How Can You Stay, Ralph describes how Carter forgot about their collaborations, calling this lapse a “brilliant cri-tique.” Later in the work, a simple dialogue, borrowed from Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film Solaris, appears on the screen with no indication of who is speaking to whom: “Did you ever think of me? Only when I was sad.” Here, emotion—sadness in particular—prompts memory rather than memory eliciting emotion. Feeling precedes its referent, as if mourning were the resting state, so that the person being remembered and invoked in Ralph’s dialogue can be filled or rein-habited by the loved one or the performer with the right talisman.

While this kind of intimacy has been understood under the sign of psy-choanalytic transference and intersubjectivity, nowhere is the ritualistic and performative character of this dynamic better articulated than in the practice of spirit possession, particularly in Haitian Vodou. What colloquially we may describe as a trance, Vodou conceives as the experience of a horse being mounted by a master—a lwa, or spirit—who allows for communication between the world of the living and the dead. In her book Haiti, History, and the Gods (1995), Joan Colin Dayan explains that Vodou is in part “the preservation of pieces of history ignored, denigrated, or exorcized by the standard ‘drum and trumpet’ histories of empire” and that it “must be viewed as ritual reenactments of Haiti’s colonial past, even more than as retentions from Africa.” Vodou links the past to the pres-ent, bringing into sensual relief the shattering terrors experienced under slavery and colonialism otherwise lost to grand historical narratives.

Vodou’s form of inheritance thus animates yet a third of Ralph’s lateral rela-tions: Marxist filmmaker Maya Deren. When in 1995 Ralph disbanded his mod-ern dance company, with its “straight legs, elongated spines, and pointed feet,” he began his ten-year project, the Geography Trilogy, by visiting the “‘invisible’. . . island off the coast of Florida” where he found himself “inventing Africa.” During a June 1996 workshop rehearsing for Geography, the first work in the tril-ogy, Ralph broached the topic of what he called “trance dancing” by showing his African collaborators Deren’s Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. While several films dating from the period after the US occupation of Haiti have made Vodou available to American viewers, Deren’s work is notable for its interest in dance and use of choreography as a filmic structure. For Deren, film structure could be informed by “‘human choreography’s’ ability to expand the technical repertoire of cinema, creating distance, suspension, and chance through choreog-raphy rather than through montage.”

Deren’s description of the possibilities for moving images offered by cho-reography reads like an annotation for Ralph’s own inquiries. Although her film—which captures rituals such as passing a chicken over one’s head to wash away impurities and evil and offering a goat to transfuse life to Papa Gede, the loa of the dead—would be posthumously edited by Deren’s widower, Teiji Ito, and his second wife, Cheryl, into an ethnographic realist style (one that did not coincide with Deren’s wishes), her accompanying book-length narrative of the same name is perhaps truer to the possibilities of “human choreography.” Much like Ralph, she too shared an interest in trance’s aesthetic experiences. Deren writes:

Slowly still, borne on its lightless beam, as one might rise up from the bottom of the sea, so I rise up, the body growing lighter with each sec-ond, am up-borne stronger, drawn up faster, uprising swifter, mounting still higher, higher still, faster, the sound grown still stronger, its draw tighter, still swifter, become loud, loud and louder, the thundering rattle, clangoring bell, unbearable, then suddenly: surface; suddenly: air; suddenly: sound is light, dazzling white.

Punctuated yet ceaseless, Deren’s language is hyperbolic, mimicking the unbeara-ble abandon of the “sudden” experience through her phonic prose. Like Ralph’s request to his dancers, Deren’s invocation attempts to translate an inscrutable experience with a surfeit of description.

Ralph asked the Geography cast to cultivate the same energies as those in Deren’s film and text—rocking, flailing, and stumbling, their eyes rolling to the back of their heads. Interestingly, each cast member refused to render expressly spectacular the history of colonialism and dispossession coded in the act of spirit possession. The stakes, they claimed, were too great; a trance performed on a proscenium stage would only denigrate the act’s integrity. In this way, the cast responded to Ralph’s request with a tactic similar to the one Haitian novelist Marie Chauvet opted for in her semi-autobiographical Fonds-des-Nègres. Chauvet tells the first-person account of Marie-Ange Louisius, a light-skinned bourgeois woman from Port-au-Prince who goes to live with her grandmother in rural Fonds-des-Nègres where she learns about Vodou. Unlike the romanticization and heroism associated with the peasant-story genre, Louisius describes bearing witness to possession in a Haitian Creole so bare it emphasizes the everydayness of the spirit world all around: “Agwe, you have mounted me, Agwe oh.” Chauvet, then, escapes an overblown description of spirit possession. Like the refusal of Ralph’s dancers—their “no” that would eventually come back as the no-dance several years later—Chauvet’s move away from describing ritual for prying eyes becomes a means of spiritual return, albeit in a different form.

No-dancing

In 4Walls, of 2012 (fig. 5), dancers Darrell Jones and Gesel Mason perform two twenty-minute solos one after the other on a sprung floor with viewers seated on all four sides. The audience may freely wander into a pendant space where two monitors screen video documentation, from two different angles, of six dancers (including Jones and Mason) performing movements prompted by the live score. Each video plays twice to last as long as the forty- minute live performance. Even in the pendant space, one can hear the live dancers’ pre- and postverbal exasperations, their unscripted nuhs, woos, and aahs we know from fucking or praying or wailing (or fucking and praying and wailing)—here forcibly displaced onto the unknowable bodies of the taped performers. Ralph calls the rotating, spinning, and pounding that make up the performers’ ever-downward motion a “dance with no form.” This name belies the intense physicality and virtuosity required of the dancers, and obscures the history that structures the no-form movement.

Where is the source of this movement? Trying to locate where Jones or Mason physically initiate reveals no clear point of origin. As a rotation becomes a fall becomes a roll becomes a strike, each is so different from what came before or will come after that one cannot register the mechanics of any isolated movement. The movements bear the traces of the everyday without being pedestrian, and carry such fierce emotional charge that detecting a movement’s physical initiation or expressive cause is impossible. The sequencing does not code an internal hierarchy or cue meaning, further frustrating our ability to see a single moment as anything other than part of one long whir. We can know the intensity and specificity of the performers’ physical exertion only in its arresting formlessness.

The movement’s only organizing mechanism appears to be its alternating centripetal and centrifugal forces, moving toward and away from a center. This center exists in both the three-dimensional space of each individual performer, who moves in circles, recursively, as well as in the planar space of the stage on which the dancers progress through predetermined yet randomized pathways. Forestalling release and resurrection, the dancers build a sense of uncertainty as if attempting to bang out a world of their own making.

Each of these twenty-minute solos has been performed under many titles. Before it was “a dance with no form,” as billed for 4Walls, it was the twenty- minute “Wall/hole” in How Can You Stay (fig. 4), and the three-minute “Ecstasy,” or “drunk dance,” in Patton. Before that, it existed in rehearsal and was prompted by keywords, including “rapture” and “transcen-dence.” In How Can You Stay, Ralph preps us to watch “Wall/hole” by recounting Patton’s “Ecstasy.” In Patton, he tells us, he “was searching for compositional formlessness—a no-style, no-dance that was, in fact, a dance.” But the no-dance’s near-trance states, its simultaneous senses of ascension and apocalypse, did not originate there.

In rehearsals for 1997’s Geography, Ralph asked his dancers to perform possession rituals; they refused, agreeing instead to imitate their out-of-body sensibility. Tracking each gesture’s emergence is a task as quixotic as finding the physical initiation for the movement. Indeed, this self-referential buildup mirrors the movement’s logic. The dancer not only moves downward but rises up, backward, to move forward. While it occurs in real time, it resembles the blur or retrogression of a video—and in particular, the way that in this mediated time-space, a fall can avoid ever quite reaching the floor.

Language holds the dance together. The work is built, unbuilt, and rebuilt through keywords that Ralph gives to his performers: “falling, not up or down”; “suspension”; “take your body apart and put it back together.” As Jones described the making of the six-dancer How Can You Stay,

We started off with improvisations based on the single word ‘transcen-dence’ or something similar to that. Then [Ralph] started to videotape it…. I think we all felt like we needed structures in order to sustain the type of thing he was talking about. So we started to go back and look at the places on the videotape where there were connections and we tried to recreate them. Sometimes that worked; sometimes that failed. The one word turned into many words.

The various points Jones calls “connections”—open mouth pressed to open mouth, kicks and holds—maintain the movement’s inertia. Eye contact, energetic transfer, and touch clarify and proliferate the meaning of Ralph’s keywords. The dancers translate these linguistic cues into movement, expressing them for each other and—for those viewers who make it to the other side—for us.

While reiteration and language internally organize the movement’s down-ward force, its meaning is accessed through narrative. At the end of Patton, before the no-dance begins, a video recorded by Ralph’s daughter, Chelsea, on the streets of Duluth, Minnesota, begins to play. The video depicts Ralph standing below a yellow streetlight, where, we are told, a plum tree once stood; there, a young man called Elias Clayton was publicly lynched in 1920. Ralph waits, then seems to lose his sense of gravity, knocking into the pole. He sits against the pole, gets up, wanders and stumbles, falls to the ground, lays down. In the live performance, Ralph speaks over the video, assuming the role of both narrator and Clayton, shifting from witness to victim and keeping the viewer’s certainty at bay:

Elias did get into trouble one summer. . .creating rituals, improvisa-tional memorials throughout the state, places where something bad had happened. He was so serious.

“This is an act of sympathy,” and that’s what he told the police officer, quoting James Baldwin. It was a really interesting idea, but all fake-finding. He would suspend his body from specifically chosen vertical objects, hang-ing, falling-in-space, not-up-or-down, falling-up-and-down from bridges, streetlights, trees. Once from an open fire hydrant. There wasn’t much falling distance, but he did get really really wet. But not here. Here was a yellow streetlight pole. And a few memories. One was of all that water.

He was arrested that summer in Duluth, on his birthday. Spent a few days in the county jail. When he got home, he made this dance.

A scrim rises to reveal a second stage with a glossy mauve curtain on three sides. Reverend Gary Davis’s song “I Am the Light of the World” plays, describing Jesus bringing Lazarus back to life four days after his death; Ralph moves to the stage within a stage and begins to perform his version of a buck dance. Gervais enters stage right with a fire hose and begins to spray Ralph as Mason enters downstage and performs the same buck dance. David Thomson, Jones, and Okpokwasili follow suit. The first stage performance of no-dance ensues, and like the trauma to which it refers, the dance repeats itself, seemingly without end.

Patton is about what Saidiya Hartman calls our capacity “to honor our debt to the dead”; about the way a gesture or a movement can hold something sharper than memory. Ralph, in avoiding monumentalizing or memorializing Clatyon, refuses to secure the certainty of his end. Elias did get into trouble one summer. . .creating rituals, improvisational memorials throughout the state, places where something bad had happened.

The rituals and improvisations are as much Clayton’s creations as they are Ralph’s violent attempts to come to terms with the unnamed and ongoing “something bad.” These physical enactments—suspending his body, falling up from bridges—are non-events. No one would recognize Ralph’s movement as a form of historical redress; unmarked, however, his counter-memorials might offer Clayton repose.

Performance is like trauma, ubiquitous and paradoxical; both repeat themselves and neither can be fully held in language; each relies on the other. In his essay “Mourning and Melancholia,” Sigmund Freud proposed that the conscious mind can revisit grief through catharsis; a failure to process trauma adequately, however, results in the perpetual and pathological unconscious he describes as “melancholia.” In Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive (1999), Giorgio Agamben describes the conundrum of recounting the truth of the horrors of the Nazi death camps as an aporia, a challenge to the very structure of testimony. “[T]he survivors,” he writes, “bore witness to something it is impossible to bear witness to.” Ralph’s Patton responds to Freud’s melancholia and Agamben’s remnants with resurrection, attending to Clayton’s loss via the “Ecstasy” of movement and African American religious song. The no-dance begins with an image of Ralph falling, an image that recalls but refuses to reenact Clayton’s body or the many documentary images of civil rights–era antiblack violence that saturate the national imaginary. Unable to withstand the hose’s water pressure, Ralph falls, gets back up, and prepares himself to be raised once again.

The Warren

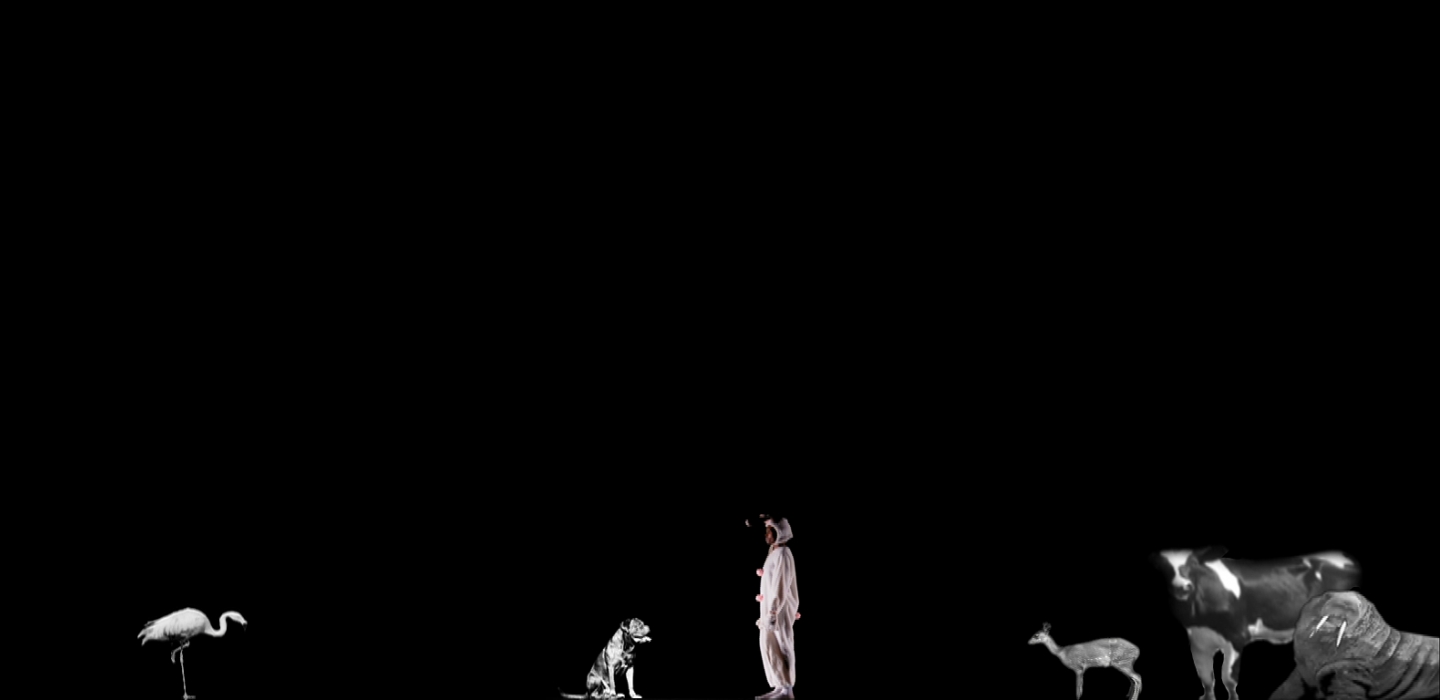

Near the end of How Can You Stay, in a passage called “Fairy Tale” (fig. 1) Ralph stages his own flight from human language. In a video projection Ralph made in collaboration with Jim Findlay, Okpokwasili, dressed in a bunny suit, kneels to face a computer-altered fleshy hound dog. In this choreographed encounter, the two animals sit with each other’s gaze. The dog approaches the rabbit. One by one, other CGI animals enter: a flamingo, a deer, a tapir, a cow, a giraffe, a walrus—a landscape of animals that do not belong together, an ecosys-tem made in excess. This video is sandwiched between an eight-minute passage in which Okpokwasili sobs onstage without narrative cause (we are told that she’s crying for all of the world’s sorrows) and the work’s concluding scene, a duet in which Okpokwasili is tasked with neither looking at nor speaking to Ralph. The passage is a kind of silence, a placeholder for chance encounters.

In Ralph’s ecology, rabbits and hares abound. A 2014 photograph depicts Albert and Geneva Johnson—relatives of Walter and Edna Carter—staring unen-thusiastically behind bunny ears in their home in Little Yazoo, Mississippi. Ralph’s bunnies—the Carter family, Okpokwasili—hijack Br’er Rabbit, the urtrickster figure of African American folklore. Although the journalist Joel Chandler Harris was the first to marshal the stories of this unreliable narrator into fiction in his late-nineteenth century The Complete Tales of Uncle Remus, Br’er Rabbit dates from several centuries earlier. Developed on the slave plantation, the rabbit is a historic figure of indirection and subterfuge.

Ralph’s rabbits may also have another lineage in which critters become political actors on the historical stage. In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), Karl Marx used the figure of the mole to narrate the process of revolu-tionary advancement. The mole, who surfaces only during periods of heightened class struggle, otherwise remains below the surface in order to dig new tunnels, in effect preparing for future periods of struggle. Moving slowly underground, the mole is systematic and swift, refusing the allure of daylight and the impositions of consciousness. Georges Bataille wrote in 1929 that “‘Old Mole,’ Marx’s resounding expression for the complete satisfaction of the revolutionary outburst of the masses, must be understood in relation to the notion of a geological uprising. . .Marx’s point of departure has nothing to do with the heavens, the preferred station of the imperialist eagle as of Christian or revolutionary utopias. He begins in the bowels of the earth, as in the materialist bowels of proletarians.” Rabbits, like moles, are fossorial, living in groups in underground burrows. Ralph’s story begins in the mud, in the Delta earth from whose gumbo he builds his characters. We go to the warren to die and to begin again.

Ralph’s work holds multiple, sometimes conflicting sensual experiences: labo-riousness and pleasure, pain and devotion, stamina and excess. His works are not only of this Earth; they are made from its undercommons. While Ralph’s reuse of objects, movement phrases, and characters could arguably be evidence of stylistic consistency or conceptual congruence, in fact they reflect his radical disbelief in tidy narratives. While Ralph’s career is often detailed as a series of breaks or ruptures—the dissolution of his company, the end of the Geography Trilogy, the death of his partner—here I have tried to describe its continuities, those elements that persist across the many names by which he has gone and the doubles, avatars, and carriers he has consistently regenerated for himself. The recursiveness of Ralph’s work not only refuses periodization—the master logic by which artistic careers and grand nar-ratives of history alike are written—but also allegorizes and instantiates history’s own formless reappearances. Indeed, Ralph the narrator appears only as a subject who perpetually disappears into history. Each writing is at once a rewriting and an era-sure, an emphatic anticipation of the future through retrogression, faith, and doubt.

The Ant’s Burden

“The Ant’s Burden,” a passage from Folktales, of 1985, opens on an empty stage. We hear the sound of birds chirping and flying, thunder cracking, rain falling. A young black boy, age ten or eleven, enters. Dressed in a Hawaiian shirt and khaki shorts, he recounts Aesop’s fable of the fox and the stork. The fox invites the stork to share in a meal, but serves the soup in a bowl, which the stork cannot easily drink with its beak. The stork, in turn, invites the fox for a meal, served in a narrow-necked vessel that the fox cannot access. Trickery begets trickery. The boy exits, and Ralph enters, suddenly, stage left, shaking as if he were trying to warm himself up or lose something off his person. After moving through a series of energetic phrases to a woodwind track, he says “oops” and leaps.

Ralph moves on to the next fable. “A father and his son were very clever farmers,” he begins, narrating a West African morality tale about a man who attempts to outsmart his son. During a drought, the son finds a dwarf able to generate rain when tapped lightly on the hump with two small branches. The father, wanting to outdo his son, scales up the size of his branches and aggressively strikes the dwarf, in hopes that the increased force would increase his own bounty. The dwarf drops dead, and the king forces the father to atone for his greed by forever carrying the dwarf ’s body on his head. But the father, ever the trickster, dupes an ant into taking on the load. Ralph narrates the story using figurines and props mid-stage, with tree branches arranged in an arc forming a small proscenium. Using the same object that brought both crops and death to his characters, Ralph constructs an environment in which to animate a miniature world: he creates a theater. Despite the patent falseness implied by the plastic toys, Ralph treats the natural world and its plastic representations equally, performing a duet with a wooden bird and pro-ducing noise from a machine that generates a moo sound.

In retrospect, the passage’s pairing of text and movement, image and narrative, functions as a codex of the many aesthetic strategies that would come to charac-terize Ralph’s work: his emphasis on storytelling; his interest in myth, folklore, and forms of knowledge that are passed down through oral and physical communica-tion; and his collaboration with self-taught and nonprofessional performers who stand in for everyday experience—and, as often as not, for Ralph himself.

In Folktales, the Harlem Storytellers, a group of African American preadoles-cent boys Ralph found at Miss Ruth Williams’s Harlem tap dance studio, fulfills this final strategy. With each vignette, they return to the stage to explain natural phenomena or describe Earth’s beginnings—to relay, as Ralph’s young surrogates, origin narrative after origin narrative under the cover of genealogical inheritance. The moral structures in these tales don’t divide good and evil into discrete, simple terms; instead responsibility for both good and bad is shared across an entire ecosys-tem. The trickster fox, for example, deserves trickery from the stork in return; the ant and the dwarf he is conscripted to carry end up in the son’s fields. Here, moral-ity is lived through narrative ambiguity, which rather than offering a way out of the brutality of our everyday lives, attaches us to one another. Drawing our attention to the small yet exhausting work of the ant and his burden, Ralph cunningly invites the onlooker to step in closer and enter his hilly field.