Tesseract Notebook

Ryan Jenkins (www.ryanjenkins.work) is a Video Engineer currently working in upstate New York at EMPAC, the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Ryan became well acquainted with Charles, Rashaun, and Silas over the development and filming of the 3D cinema version of Tesseract. Ryan took part in the planning of the stereoscopic feature, and was the primary camera operator. As their relationship grew and the live version of the show began to take shape, Ryan was asked to take part in it as the live video Steadicam operator. Working collaboratively to combine the unique capabilities of Steadicam with the video work and choreography, the group found new ways and languages to combine their three fields into a working collaboration.

As a steadicam operator, Ryan has had the pleasure of exploring the choreography of camera alongside the choreography of dance. We thought it would be an interesting insight into the work to hear from an operator with no traditional dance training, and how he developed his own language and notation to document the work. Included here are various versions of Ryan’s notebook that he kept specifically for this project. In it, he tracks changes and variations in the camera choreography over the development of the work, and his own vocabulary to understand the movement of the bodies on stage.

I keep a lot of notes. Most of them end up being reminders or things that should have been entered digitally so I don’t lose them. Sometimes they mean nothing and are simply driven by the enjoyment of handwriting and doodling; I have trouble focusing if I’m not drawing.

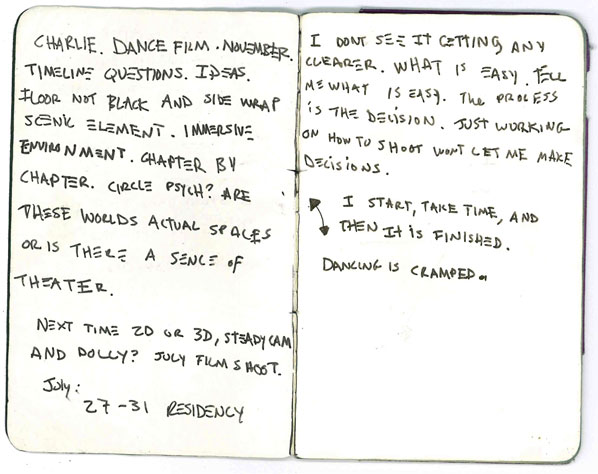

I have had the honor of being part of the development of Tesseract (the 3D film and the live performance) since the beginning. These pages are short notes from the first time I actually met Charlie and the very vague beginnings of what we wanted to do with the film. I made careful note of some of the phrases he used in describing his process and how we were going to approach the residency and shoot because I found them quite beautiful in their simplicity. His undertaking, to edit and make a 3D film with hardly any post-production support besides his assistant Lazar Bozic, was truly monumental. I don’t think any of us knew how complicated the process to edit and compose in 3D was truly going to be, and I will always be blown away by how it all came together.

I grew to greatly respect Charlie’s understanding of his own workflow and practice. With such a big production there is a lot of stress put into “knowing what you want it to look like” from a director of photography/operator perspective. When I was trying to tease this information out of Charlie in a meeting leading up to the shoot he said, “I don’t see it getting any clearer. What is easy? Tell me what is easy. The process is the decision; just working on how to shoot won’t let me make decisions. I need to start, take time, and then it will be finished.”

I have been so impressed and inspired by how the technology and complexity of this project has remained secondary to the collaborative artistic visions of Charlie, Rashaun, and Silas. It is one of the few projects I have been involved in over my 10 years as a technical video engineer in which the combination of so many “wow factor” technical elements fades into the background instead of acting like a crutch to captivate the audience.

I am not a trained dancer, but as a Steadicam operator I am well versed in following precise choreography. All the Steadicam shots in the live Tesseract show are on a fixed zoom and focus distance, so it is imperative that my spacing and positioning remain as identical as possible to how we set the cameras up. While this rig is incredibly light by Steadicam standards, it is still a good 20 pounds and I must constantly be aware of dancer positioning to avoid hurting anyone or jeopardizing the video feed with shakes and bumps.

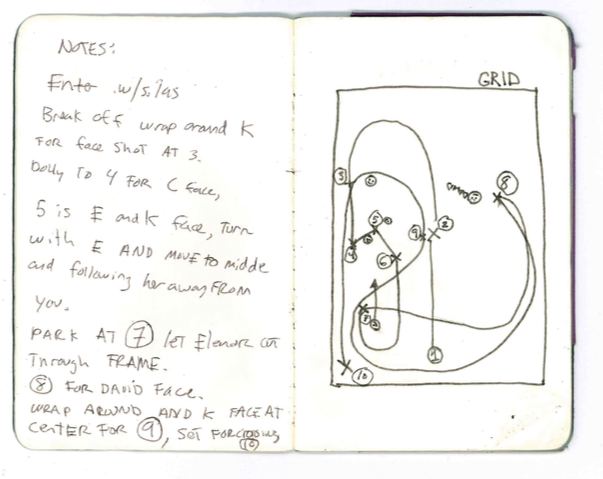

Shown above are the key locations in the opening Steadicam section. I believe it is labeled “grid” here but the dancers call it something else. The choreography is linked between the camera and dance, but since my training is not classically in dance I had to find my own way to notate, time, and label all of the sections. Also, while things change as the show evolves, most of the choreography was fleshed out well before I entered the picture, meaning I ended up needing to create my own placemarks and vocabulary for how I fit into the work. It became my job to lend my knowledge of how the Steadicam moves and its benefits over traditional camerawork to help guide the camera choreography from a cinematic standpoint, all the while taking feedback and direction on my presence on stage and how that needed to be altered to fit the dancing.

I think of this section as the formal introduction to the projection surface, as well as an introduction to the dancers via their framing. Each dancer gets their own version of a close up in this section, as well as a substantial amount of medium-to-wide shots to introduce the entirety of the stage to the audience and to establish that this is clearly a live video feed from me.

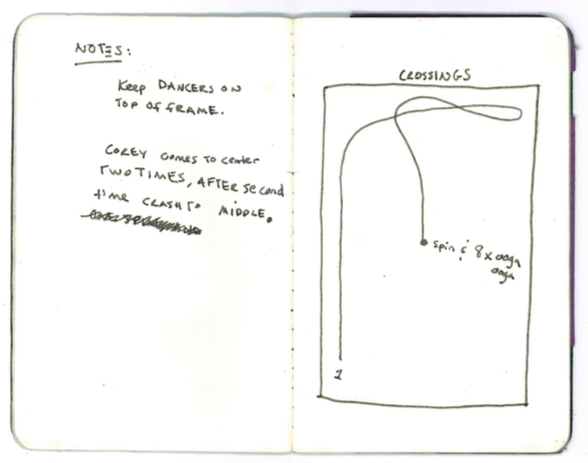

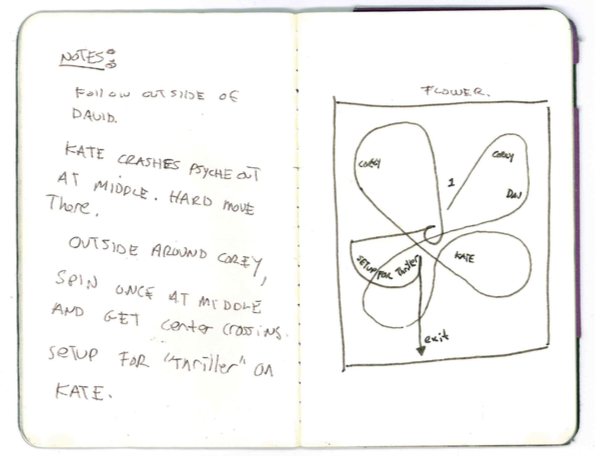

“Crossings” follows the grid pattern, introducing the “baby steps” that I use as a Steadicam operator to limit the movement of my hips and increase the rig’s stability. It is a rather slow march across downstage in which horizon and framing are crucial; the movement is so subtle in the camera that it is very easy for even an untrained eye to pick out problems. This is also one of the shots in which the marley tape and the upstage wall are most likely to be visible, so the camera horizon on the giant scrim sticks out like a sore thumb if the camera is not completely level. After “Crossings” I make a wide swing to centerstage right and reenter the scene with Silas, following him and crashing to middle where the camera does multiple spins surrounded by the dancers. I wrote this down originally as the “Ooga Ooga” and it quickly morphed into the “Ooga Booga.”

Post “Ooga Booga” is the most technically difficult movement for me in the work. The scene starts with a crashing fall towards Cori, which initiates a figure eight-style pattern that revolves around each dancer. The dancers and I all take turns cutting through the center of the stage, so timing is specific in order to not have an accident. The scene ends with what I refer to as the “Thriller” scene, with Kate leading me off stage in a traditional “Don Juan” Steadicam shot.

I have to cover a lot of ground in this section, but still maintain complete control of the rig in very close quarters with the dancers. This usually means I try to run in as reserved a manner as possible in order to minimize bounce transferring up the camera arm. It ends up being a balancing act between camera stability and my ability to keep up with the dancers and hit my marks. Depending on the size of the venue, these larger flower petal sections above become bigger or smaller and the distance and speed of the run has to change accordingly.

I am very confident in my spatial awareness with the rig both in its relationship to the dancers and the stage, but it is something I worry about constantly. I had a great discussion with Kate in a taxi ride back to where I was staying after our run of shows at the BAM Next Wave Festival, where she confided in me her apprehension early on in the project; she explained how ominous the giant metal camera rig felt as it whipped around them, how much damage it could inflict both on their persons and on their careers if something bad were to happen. I feel honored that I have been given the time and opportunity to prove to them my capabilities as a nondancer, and that I have been able to share space on stage with them. I hope I do them and the history of their work the justice it deserves. It’s rare as the never-seen camera operator to have the opportunity to interact with your subjects and develop a performative relationship with them.

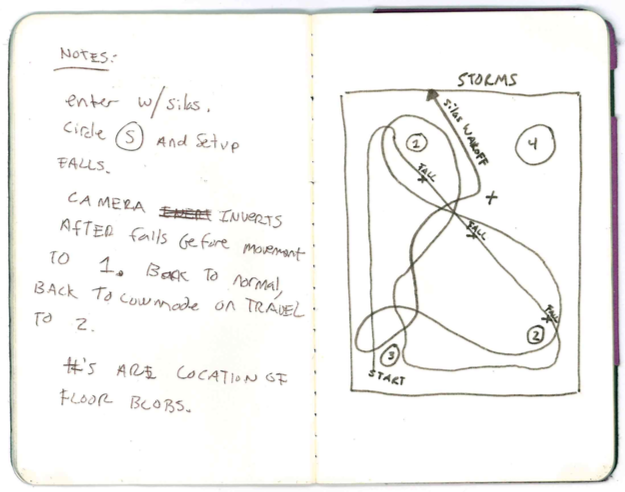

During “Storms” the camera is completely inverted, and we switch to low mode on the Steadicam. There are only about three or four minutes (or so it feels) between the end of the previous Steadicam section and this one. In that time I need to exit stage left and wrap around whatever back exit the theater has in order to get to stage left. Once there, I have to rebalance my Steadicam into low mode and prepare for my entrance. This drawing is not actually up to date as of this writing; it represents the original version of the show, as it was performed at EMPAC, The Walker, and the MCA Chicago. Since then there have been multiple changes but the concept remains the same.

Of note in the drawing are the four major “puddles” or “blobs”: locations of centralized action that I try to orient myself around to cover the groups of dancers. The “Fall” note is when we do a domino-like effect of the dancers falling to the ground while I run past them as the camera flips from vertical to upside down. In this drawing it has my entrance from stage left, which was much easier than it is now, where I have to exit the theater and run around to the other side for my new entrance.

We try to avoid ever having the camera see the scrim downstage, as it would create an infinite mirroring effect on the projection side of the screen for the viewer. In this section it is particularly difficult to have the camera so low to the ground and capture the dance without ever having the silver scrim come into frame. The angle that I need to pan up while moving is small but since it originates at roughly my knees, I have to be conscious of the edges of my frame in order to exclude the scrim. The rest of the show feels very geometric and precise to me, and I quite like how this section has a lot more inherent flow to it, even in how I hold the rig and operate it.

I think we all wanted to explore what utilizing the Steadicam’s ability to invert in a live situation would do for Charlie’s visuals as well as for the viewer. A lot of the camera work was built around the same geometric shapes and patterns the dancers are using, only going in with a cameraperson’s eye and saying, “Where can I find something beautiful here, and how do I maintain that while getting to my next spot?” This is kind of the reverse of how I normally work, where the framing denotes where you move and everything else needs to shift and accommodate your body and the lens position.

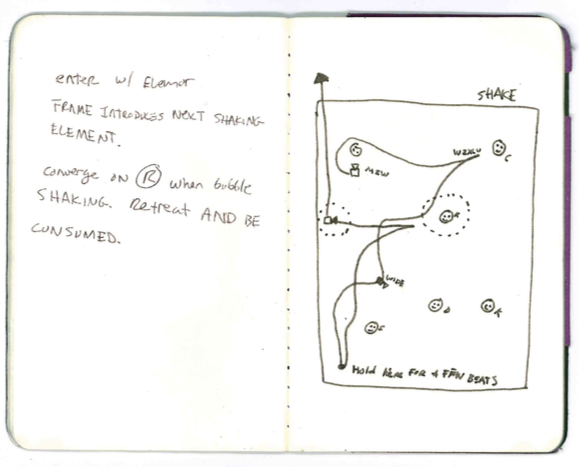

I don’t think the end has a name other than “The End.” Sometimes I call it “The Snake.” By the time I get here I am pretty relaxed, the hardest parts are over and all I need to do at this point is not trip on myself and rely on everyone to pick me up! The original version of the ending was called “The Shake” and had a very different feeling, driven by Charlie’s video effects. It was much more staccato, and rather than focusing on Rashaun after his solo the camera worked more like a dolly shot that traversed the width of the stage before being consumed, the dancers circling around me and drawing me off stage. Very soon into the development of the show this turned into a lift, and we had to work out the logistics of the Steadicam apparatus and myself being lifted and rotated above the dancers’ heads. Thankfully I am a stick and hardly weigh anything. I was pretty nervous at first about getting picked up and spun around, and in a way it’s a nice return to the differences in our practices on stage; lifts for them are bread-and-butter while I have never been lifted wearing a camera before, nor ever considered it feasible.

I really cannot say enough about how amazing it has been to be part of this whole production. Being the camera operator on the film itself was a great learning experience for me, and I learned so much from Charlie, particularly how he looks at filming dance. We eventually came to a point in developing the live show where he would give me suggestions and then just say, “I trust you to find what you need to make it work”—then I would head over to my Steadicam stand, beaming for awhile. He was always respectful of me and my opinions, despite how established he is and how particular about framing and the look of shots, and that means a lot to me. I so often work on projects with very tight schedules; being able to really develop a bond with the crew for this project has been such a treat, one I look forward to every time I get to be in a room with them all.