Contact is Crisis: A Choreotechnoarchaeology of Clytemnestra

The NSA is not even close to cracking the code of choreography; it’s really the most effective place to embed important, secret information.

—Michelle Ellsworth

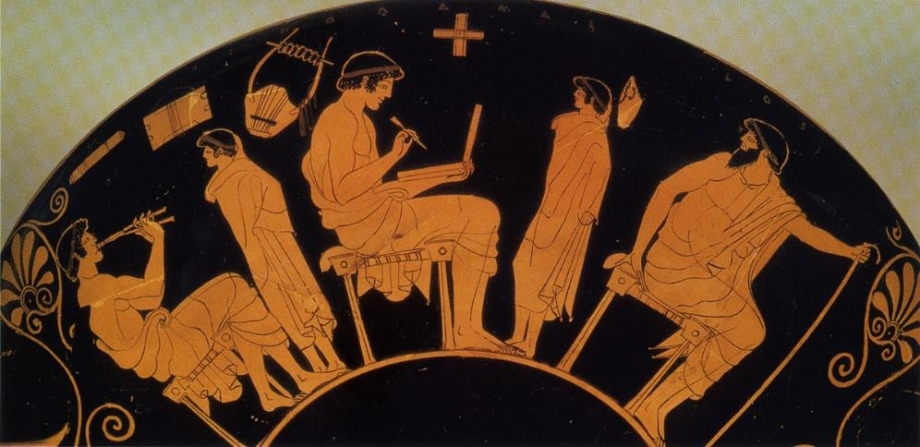

Clytemnestra gets 599,000 Google results in .41 seconds, and this is how Wikipedia knows her best. But she is also accurately Klytemnestra (30,400 hits; .53 seconds), Klytaimnestra (46,100 hits; .64 seconds), Clytaimnestra (14,000 hits; .56 seconds), and Clytaemnestra (62,200 hits; .65 seconds). Nor is this slippage unique to English orthography; substitutions, additions, and deletions have long attended this figure from Greco-Roman myth. The oldest nameable ancient Greek poet, Homer, named her over 2,700 years ago; in his Iliad and Odyssey epics she is Klytaimnestra, wife of Agamemnon and treacherous foil for Penelope, loyal wife of Odysseus. Her Homeric etymology—klytos, “famed” + mnester, “suitor”—defines her as “famed for her suitors,” which is ironically the enduring reputation of Penelope instead. But these Homeric roots are a sinister reference to the courtship of Clytemnestra by her husband’s cousin Aegisthus, and the violence born of their infidelity. The tragedian Aeschylus layers in a complication 300 years after Homer: in his Oresteia trilogy she is Klytaimestra. By dropping the letter nu from her Homeric name, Aeschylus shifts her fame from her ill-fated family affair to her clever mind: klytos + mestor, “advisor,” “counselor.” As an early-5th-century Athenian painter made literal on a wine cup—where her inscribed name is interrupted by axe blade and handle, by head and extended arm—violent intentions and intervening bodies have long shaped Clytemnestra’s identity and experiences. For nearly three millennia, technologies have rendered her instable, uncertain, volatile.

Layers and complications are the bread and butter of dancer/choreographer Michelle Ellsworth’s engagement with Clytemnestra. Or, more accurately, they are the bun and the burger. And this burger comes loaded. “I have a relationship with burgers,” says Ellsworth, they have “all the potential of torture and craft and intimacy” ;so too, her Clytemnestra.

Young Clytemnestra was already existentially complicated. Her mother was Leda, beautiful wife of mortal Tyndareus. By popular ancient account, king-of-gods Zeus disguised himself as a swan and raped Leda, fertilizing her egg with twins. A century ago, Yeats inscribed the act: “A sudden blow: the great wings beating still / above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed / by the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill, / he holds her helpless breast upon his breast.” On the same dark, helpless night, Leda lay with Tyndareus and a second egg with a second duo began to grow alongside the first; a twin twinning. The two born of Zeus’ animal attack were Helen, eventual cause of the Trojan World War, and her brother Polydeuces; those from the mortal egg were Clytemnestra and Castor. The fraternal twin sisters grew up to wed the brothers Menelaus and Agamemnon, additionally bound by the curse ensnaring their in-laws. Clytemnestra was thus locked into a criss-crossing fate sown in the moment of her mother’s rape: “A shudder in the loins engenders there / the broken wall, the burning roof and tower/ and Agamemnon dead.”

There is nothing safe here.

Ellsworth is thoroughly versed in the Classical history of Clytemnestra. She dances and snaps and swipes and speaks a Clytemnestra into being who carries all the baggage of the western tradition. But she moves deftly out from under the great beating wings of antiquity to offer a fresh course. Ellsworth claims of her performance patois, “this is all language from [Robert] Fitzgerald’s translation [of Homer], so it’s, like, legit, and has a built-in integrity, which I love.” Yet this is a teasing snare. She doesn’t perform Fitzgerald’s language exactly, but a mimesis of it; phrases evolve from fixed ancient formulas into familiar but new arrangements, as when Aegisthus flatteringly calls Clytemnestra “pleaser of gullets and tongues,” or when he notes the “sharp-tipped arrowedness” of her stress. By rearranging and reproducing such archaizing language herself, Ellsworth shifts the authority of the Classical tradition’s masculine voice, and whatever legitimacy and integrity it carries, to her own—and to Clytemnestra’s. Refuge and rehabilitation become possible for a woman made vulnerable by the western canon, born of crafted infidelity to the language that shapes it.

Marriage to Agamemnon accelerated Clytemnestra’s undoing. The winds driving the Greek fleet east to retrieve Helen from Troy had died down and their revival required a virgin sacrifice. Ignorant of the mandate and tricked by her husband, Clytemnestra sent their maiden daughter Iphigenia to the waylaid convoy for what she thought would be marriage to glorious Achilles; Iphigenia became the sacrificed bride of death instead. Mother’s grief gave way to rage and vengeance, and Clytemnestra stepped out of her marriage into the arms of Aegisthus for the ten years that Agamemnon slaughtered and pillaged at Troy. At last, a technology of fiery contact broadcast the Greek victory and Agamemnon’s return to Mycenae. The blazing beacon first ignited by the triumphant Greeks at Troy set off the lighting of successive semaphores across the vast distance between Troy and Mycenae; flare gave rise to flare, “torchlight messengers, one from another running out the laps assigned,” until the news reached Clytemnestra and kindled her murderous design. On arrival at Mycenae, as Aeschylus staged the drama, Agamemnon and the captured Trojan princess Cassandra were killed by Clytemnestra and Aegisthus: the domestic terror unfolded in the bathtub, an axe-blade delivering the decisive blows. Technology is contact, and contact is crisis.

“No breaches of security and no drama” are nevertheless offered Clytemnestra by Ellsworth, who, as self-described National Security Artist, insulates the heroine from contact with others through technological interventions. In the Phone Homer recorded at On the Boards in 2012, a home-bound Clytemnestra takes Skype calls from Agamemnon and Helen at Troy, from Penelope in Ithaca, and from Aegisthus nearby, seeking her bed. Between each stressful contact she self-soothes with online shopping, self-help tutorials, and TED talks. She orders burgers for delivery (a Caduceus burger from Hermes Burger, a Liver burger from Prometheus Burger, Tartarus’ Mini Burger Biscuits; she skips over ads for Sisyphus Burger Recovery, 12 Uphill Steps). She buys a Male Gaze Simulator as surrogate for her inattentive husband; she buys a torture kit. She seriously contemplates escape by suicide and by mariticide. But in the end, she dismantles the Male Gaze Simulator, uninstalls Skype, and pulls the plug on the internet. She stops participating.

Ellsworth has reoriented Phone Homer’s conceit of disconnection several times since creating it in 1999. In the wake of the 2016 presidential election, and once Ellsworth began considering Clytemnestra and Melania Trump in relation to each other, the piece earned a new subtitle: Clytemnestra’s Guide to Surveillance-Free Living. Taking her cue from Clytemnestra as “one of the oldest and first recorded First Ladies,” Ellsworth, looking every bit Robin Wright as Claire Underwood in House of Cards, makes her own First Lady agenda explicit: to increase the “sovereignty, security, and mental health of individuals everywhere,” by means of a completely offline, surveillance-free, human-free life. She detaches Clytemnestra’s connected and deeply dangerous world; it is now of her own, safe making. The sites she browses, and their pop-up ads, are by her, for her; she scrolls through an alternate New York Times consisting of endless pieces on herself and her favorite salmon recipes. The 1s and 0s of binary technologies do service instead to her $11.11 burger order, her $1,110.11 PayPal balance, her $11.01 Lamentation Dance Tubes, “a ‘second skin’ to protect you.” By replacing Clytemnestra’s internet with an innernet, Ellsworth protects her from a world in which language and technology are as contested as ever, and as political.

Sealed safety was an especially tricky business for the women of classical antiquity, whose bodies were analogized to leaky vessels ;nevermind that Pandora’s breached box unleashed all evils onto humankind. Thus, Clytemnestra orders a PythagoDress ($1,111) advertised for its interiorities: “sometimes a girl needs a uterus, sometimes a girl needs to retreat and return to the womb. Not a problem, you have the PythagoDress. Boom, we’ve got it covered.” Step seven of the “This Cookie Recipe Isn’t That Bad” recipe on Clytemnestra’s Passive-Aggressive Pastries blog is:“Put into zip-lock bag. The sealed plastic helps maintain the freshness of your thoughts.”

The farther the withdrawal within, the safer the prospect.

Rescue was ever unavailable to Classical antiquity’s Clytemnestra. Over a thousand years after her legendary death, the 2nd-century-CE travel writer Pausanias recorded her ultimate, ignominious undoing. Describing the magnificent Bronze Age burial monument known then as the Tomb of Clytemnestra (c. 1250 BCE), he observes, “Clytemnestra and Aegisthus were buried at some distance from the wall [of Mycenae]. They were thought unworthy of a place within it.” Clytemnestra’s destabilization and destruction—including her own death at the hand of her avenging son Orestes—served a dominant, male tradition, overtly concerned with maintaining control.

And control over language and technology were essential to the effort. Inserting her body and her voice into the conversation, Ellsworth deftly flips the script with layers of inversion and reversal and innovation. On the ancient Greek stage male actors played female roles since women weren’t allowed to perform. But in Phone Homer, Ellsworth takes all roles and thereby full, revivifying control over Clytemnestra and the language and technologies that shape her. By untangling Clytemnestra from her binding nets, Ellsworth dances and scripts a powerful, timely, free way forward.

-

Phone Homer: Clytemnestra’s Guide to Surveillance-Free Living, University of San Francisco, September 28, 2017.

-

William Butler Yeats, Leda and the Swan, (1923).

-

Ibid.

-

Phone Homer: Clytemnestra’s Guide to Surveillance-Free Living, University of San Francisco, September 28, 2017.

-

A system not too conceptually distant from Senator Ted Stevens’ 2006 metaphor for the internet as a “series of tubes...[that] can be filled and if they are filled, when you put your message in, it gets in line.”

-

Aeschylus, Agamemnon, trans. Richmond Lattimore, 312-3.

-

“Contact is crisis.” Anne Carson, “Putting Her in Her Place: Woman, Dirt, and Desire,” in Before Sexuality: The Construction of Erotic Experience in the Ancient Greek World,” ed. D. M. Halperin, et al., ( Princeton University Press, 1990), 135.

-

Phone Homer: Clytemnestra’s Guide to Surveillance-Free Living, University of San Francisco, September 28, 2017.

-

A Twitter employee’s last act on the job in 2017 was temporary deactivation of the President’s account, which he has used to threaten nuclear war repeatedly. Members of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities resigned that same year with a letter that spells out “RESIST” in acrostic; the later classical and hellenistic Greek poets and the Romans after them played with acrostic, e.g., spelling the name of the author or an emperor in acrostic in the poem’s first lines. The form has a long (almost exclusively male) literary and political history.

-

See, e.g., Francois Lissarrague, “Women, Boxes, Containers: Some Signs and Metaphors," in Pandora: Women in Classical Greece, ed. E. D. Reeder, (Princeton University Press, 1995), 91-101.

-

Hesiod, Works and Days 60-82; Theogony 571-602.

-

Phone Homer, On the Boards, Seattle, WA, May 17, 2012. The reader who wants a PythagoDress and cannot find one might try instead the Barefoot Dreams Cozychic Covered in Prayer Throw Blanket available (as of 9/2017) on QVC for six easy payments of $41.67: “cover yourself,” keep yourself “safe and protected,” says the salesperson, “it comforts me,” it’s “perfect for a bride, a young girl, your mother, your mother-in-law.”

-

Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.16.7.

-

See, e.g., Froma Zeitlin, “Playing the Other: Theater, Theatricality, and the Feminine in Greek Drama,” in Nothing to Do with Dionysos? Athenian Drama in its Social Context, eds. J. J. Winkler and F. I. Zeitlin, (Princeton University Press, 1990), 63-96.