On Michelle Ellsworth’s “Phone Homer: Clytemnestra’s Guide to Surveillance-Free Living”

Phone Homer: Clytemnestra’s Guide to Surveillance-Free Living is a performance that Michelle Ellsworth began developing and presenting twenty years ago. Since then, it has evolved through different iterations to become the piece you see here. Be warned: the piece you see here isn’t the final version. In fact, there isn’t a final version, nor will there ever be. It’s not unusual for theater artists to create works that can be readily remounted—from a script, or choreographic notations, or some other documentation; over time, these works may suffer the “resuscitation effect,” looking like relics even when they’re live in front of us. Ellsworth, however, is a consummate here-and-now artist, belonging to the tradition of performers who embrace the fleeting nature of a work of live art—who craft pieces that will be new, distinct with each presentation. For Phone Homer, she upstages the passing of time by building content-rich websites and multivalent worlds—loopy, intricate, and ever-expanding—that she revisits and remaps in the now of every performance, improvising inside of a rough outline. Of this performance, one might joke that Ellsworth never steps in the same stream twice.

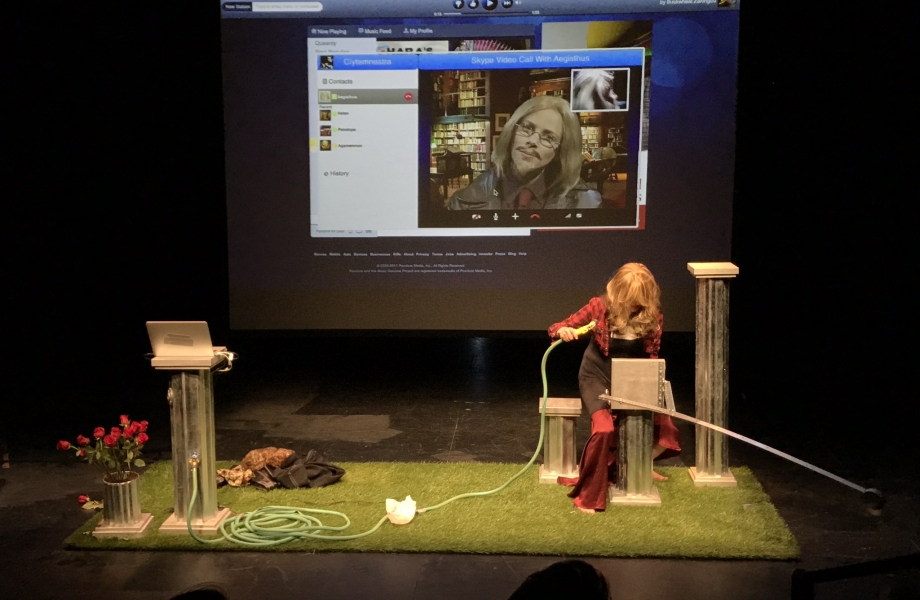

In earlier incarnations of this piece the artist plays Clytemnestra, Queen of Argos and wife of King Agamemnon, who led the Greeks to victory in the Trojan War. While he’s off killing and plundering, Clytemnestra’s left at home, bored and angry. It’s a rigged gig to be a woman stuck inside a hero’s journey. What’s a girl to do when she’s given so little to do? To bide her time, to calm her nerves, Ellsworth’s Clytemnestra goes online, orders burgers, researches answers to oddball questions (“What to do when your burger arrives?”), and plays music from her Pandora account. She also Skypes with friends and family, including Aegisthus, her husband’s cousin for whom she feels a certain frisson, and Helen, her bombshell of a sister, whose kidnapping started the entire war. In Ellsworth’s hands, a Greek tragedy becomes a comedy about marriage and failure.

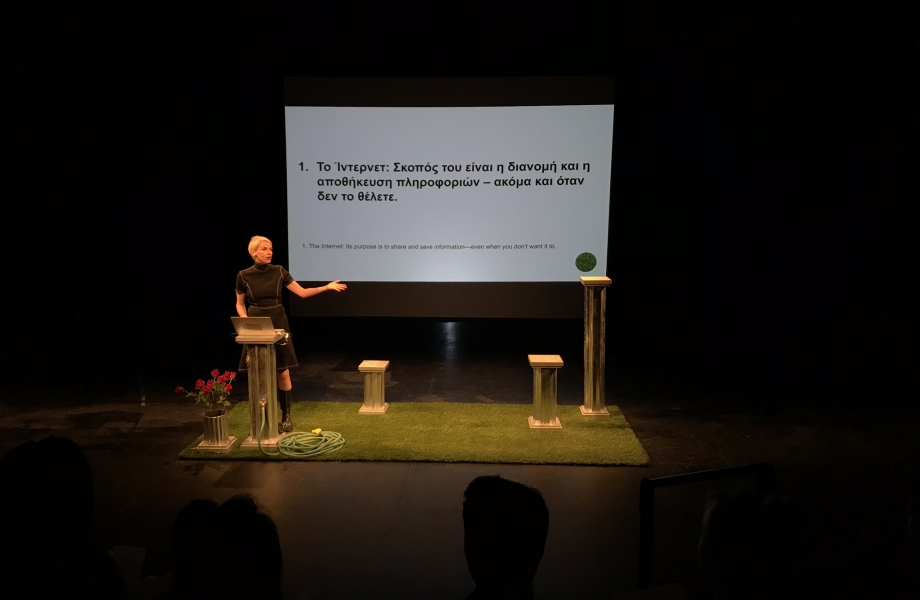

Now, Ellsworth takes the stage as herself-as-Clytemnestra, delivering a multimedia lecture on both the complexities of being a First Lady—a woman who suppresses (or not) her own desires to serve patriarchal power structures—as well as on the benefits of surveillance-free living. The artist, perhaps more Virgil than Homer, takes her audience on a tour of the online realms she has designed to keep herself quarantined from any contact with the real world, surrounded only by her stories and characters and information and products. Ellsworth’s is a breathless journey to the outer-limits of selfie-consciousness—a classic tale for our Era of Algorithms—where she spins around and around in an endless, epic feedback loop of her own making.

Ellsworth has long worked and thought and created at the intersection of self and technology, playing among the many paradoxes of what it means to be a thinking, feeling, imagining being expressing oneself, preserving oneself, via machines. Her online Motivational Video Archive is a collection of dozens of self-pep talks she’s recorded over decades on myriad subjects such as “Ex Is Getting Remarried,” “Dump Your Friend,” “Admit You Want It,” “Not Feeling Good Enough.” In each, she looks directly into the camera and speaks. “I know how you feel. I totally know how you feel,” she says in “Feeling Depressed,” staring tearfully into the camera, “Darn, I’m sorry.” She shares the videos with others, even though she ostensibly makes them for herself; the results are tender and generous, as well as distancing, safe. There is real poignancy in faux intimacy such as this. Ellsworth’s exercise in self-soothing—her talking to herself—inevitably points to the absence of a loved one, of an other who might offer the same solace.

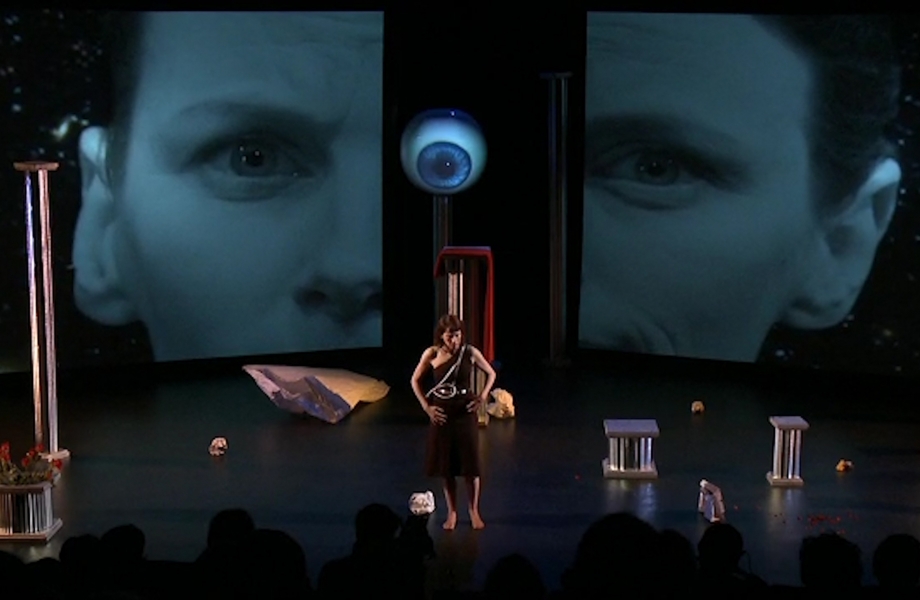

The outsourcing of human connection is one thread that runs throughout her work. In her website Choreography Generator, visitors can select pre-recorded video clips of Ellsworth and others dancing, then hit play to watch “their dance” performed for them—hardly the same as sweating it out for weeks in a rehearsal space. Preparation for the Obsolescence of the Y Chromosome is part performance, part website in which Ellsworth offers ways to navigate a world without men with the help of online resources, prosthetics, and accessories such as “The Male Gaze Simulator,” a giant digital eye that will follow a woman’s every move. There is also a giant spoon for, of course, spooning.

You’ll notice some of these same props and themes appear in Phone Homer. Part of the joy of immersing oneself in Ellsworth’s singular performances is keeping an eye out for elements that knit discrete works together. The devil is in the details; if you happen to find something eerily similar about Aegisthus, Helen, Agamemnon, and the other characters who appear via Skype to chat with Ellsworth-as-Clytemnestra, note: the artist plays every character in a chameleon-like disappearing act, in performances she recorded in 1999. (In this way, similar to her Motivational Video Archive, you’ll witness Ellsworth speaking with herself, to herself, across time.) Note also the garden hose with a small camera installed in its spout that she uses on occasion to speak with them. The punch line of this prop? Every conversation with her alter egos requires her to make the clownish gesture of shooting herself in the face, again taking aim at the absurdity—the stunting security—of conducting conversations only with oneself.

As brilliant and weirdo and hilarious as Phone Homer is, it is as well a labyrinthine hall of mirrors built inside “the worried place,” as Ellsworth sometimes calls it. Anxiety too is at the magma core of Ellsworth-as-Clytemnestra’s world. Her jitterbug mind cannot settle; her synapses rapid fire in every direction. Building her own Internet was not only an attempt to preserve her sovereignty, her autonomy; it was also a coping strategy to navigate sadness, solitude, loss. At the end, once Clytemnestra’s story has spun out, Ellsworth sings a revised version of Evita’s “Don’t Cry For Me Argentina,” paying homage to “the queen that is really a pawn.” As she stands center stage, nervously belting out her anthem for a woman whose tragic fate is that she did not recognize her own power, we—Ellsworth’s audience—revel in the vision of an artist at the height of hers.